Woodstock Library

We were recently invited to be artists-in-residence at Woodstock Artists Association & Museum by Tara Foley, WAAM’s Director of Education and Public Programs. This created an opportunity for us to begin a conversation with the Woodstock Library.

Tara connected us with the library director Ivy Gocker and children’s programming librarian Hollie Ferrara, who were excited to become partners in our project. They informed us that the Woodstock Library will be entering a major transition during the period of our residency. After many years of planning, community discussions and complications, the library is moving from its longtime site at 5 Library Lane to a new, larger building at 10 Dixon Ave in Woodstock. They will close their doors for just over a month before reopening at the new location in early autumn.

Ivy and Hollie gave us a tour of the future library building. Usually, our ideas are built around the densely packed spaces and adaptive shapes of libraries. In this case, we have been presented with a blank slate. We don’t have a clear image of the way that the Woodstock Library will fill out its new premises. As the library gains some well-deserved room to breathe, but loses its familiar old setting, we are considering how our project might help the new building establish local roots.

Our initial visit to the old location in January 2025.

Speaking with Ivy about plans for the new space.

Our residency at WAAM

We are transforming the YES Gallery into an active research and design studio. For the duration of our exhibition, we will be present in the space every Thursday from 2-5 pm to track discoveries and emerging ideas about forest collapse in Woodstock. Looking at historical and present-day relationships to the changing forest, our research will inform a proposal for a permanent public artwork at the new Woodstock Library. We hope to have conversations with library patrons and the broader public throughout our time at WAAM.

Week One:

Our first day in residence at WAAM was incredibly generative. We spent some time with Alf Evers’ Woodstock: History of an American Town which offers a look into how the landscape was shaped in the first few centuries of permanent settlement.

For many, the history of Woodstock begins with the establishment of the Byrdcliffe and Maverick arts colonies in the first few years of the 20th century. Yet, the landscape that Bolton Brown, Hervey White, and Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead carefully selected as the setting for a utopian experiment was actually deeply altered.

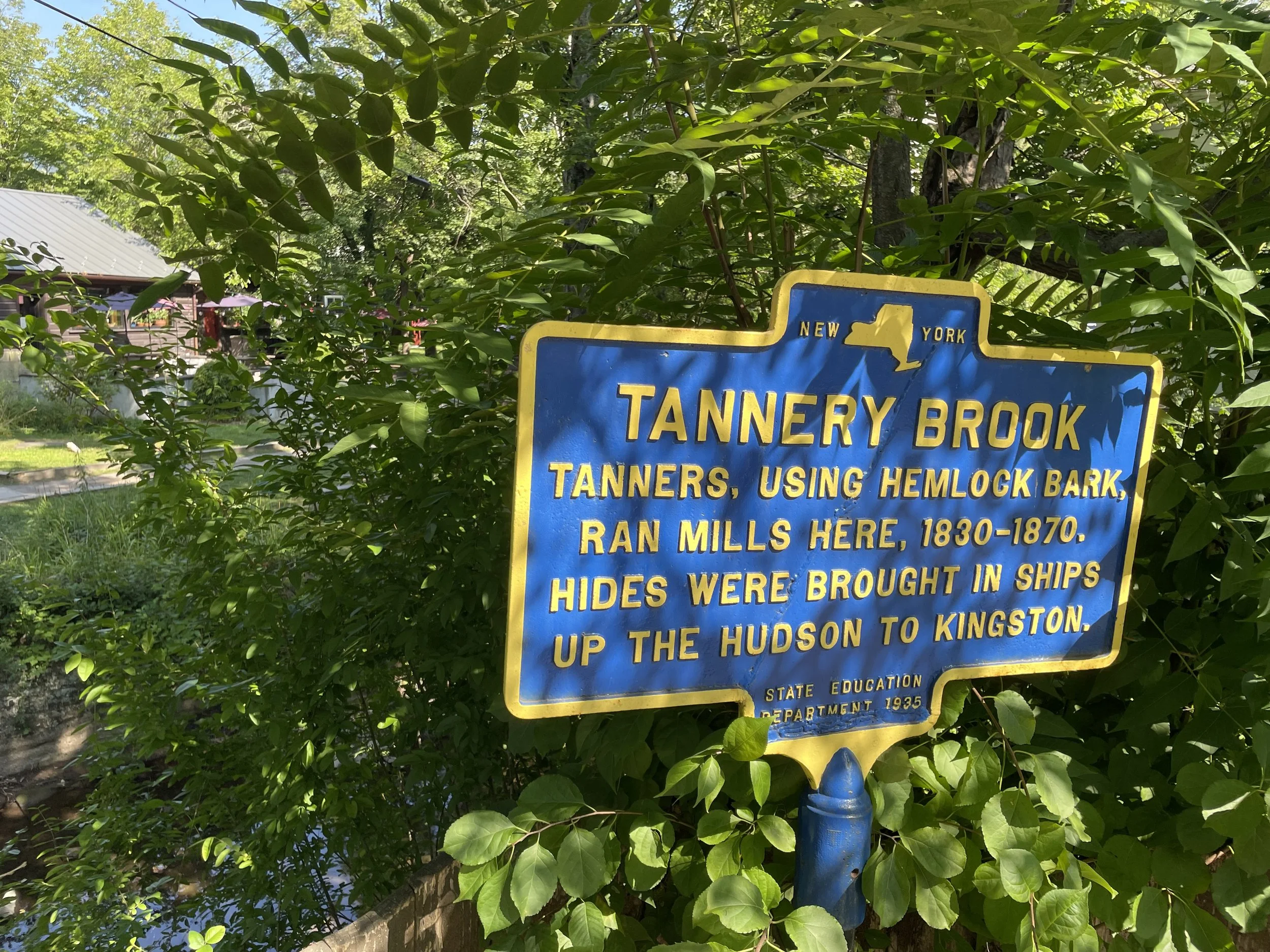

The impression of over a century of forest extraction must have been evident everywhere: felled and peeled hemlock trees rotting on the ground, or absent entirely after being shaped into shingles; hardwood sprouts with multiple small trunks being cut back repeatedly to make hoops for securing barrels; a heavily polluted waterway known as Tannery Brook with trout populations in decline…

Later, we had a surprise visit from Leslie Gerber, a trustee of the Woodstock Library and Mid-Hudson Library System. He sat with us for a conversation about the project, and expressed the depth of his own relationship with trees. Leslie was enthusiastic about the project, and invited us to introduce our work during a library board meeting happening that evening.

After a few more drop-ins from friends and others, we decided to go for a walk on the trail ascending Overlook Mountain. Perhaps the most iconic feature of the Woodstock landscape, this path is well-worn, and the mountain itself appears again and again in the writings of Woodstock’s historical residents.

We noticed that the Eastern hemlock trees in the forests of Overlook are suffering intense infestation from the hemlock woolly adelgid. Every single bough of hemlock needles we looked at or passed beneath was covered white wool-like tufts—egg sacs—and most were grayish green and sickly. Some had entirely shut down connection with the tree and turned brown, rotting on the branch. Lots of hemlocks had already fallen and were lying on the ground.

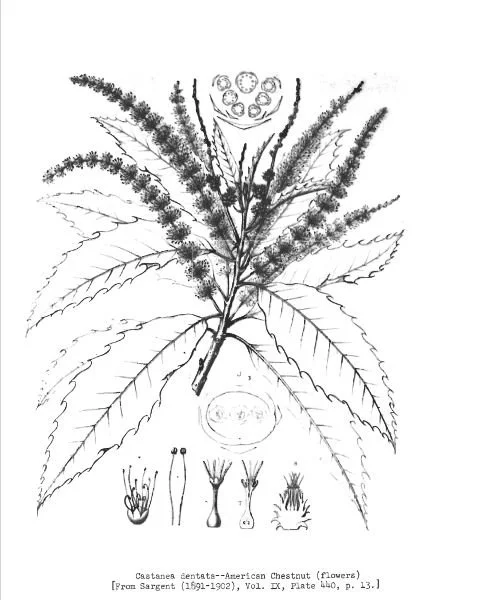

There were numerous American chestnut stump sprouts growing beside the trail. As soon as we picked up on one of those beautifully serrated leaves, we saw more and more. The tallest of the young trees we saw were 15-20ft tall, but very thin. It seems like in most forests that have been preserved since the early 20th century we can reliably find young chestnut trees. They return again and again from the same stump that originally succumbed to chestnut blight—before falling into decline themselves.

Week Two:

This week, we found ourselves thinking about the history of American chestnut in Woodstock. Chestnut blight was discovered in New York in 1904, and within a few decades all mature trees had succumbed. The stump sprouts on Overlook Mountain today come from the same roots that supported adult chestnuts until their final collapse. Did carriage-riding passersby in the early 20th century notice the extinction unfolding around them? Does anyone notice what’s left today?

The persistent presence of these short-lived sprouts helps us imagine the former forest. Woodstock’s early artists were working among dying American chestnut trees, and, we soon discovered, sometimes used the remnants for their own work.

Before heading over to our research space we stopped by the Woodstock Library. This would be our final visit to the original location. As I write, the library is having its final service day on 5 Library Lane before the month-long moving hiatus. Ivy loaned us a few books from the Local History collection, including some useful materials on Catskills botany.

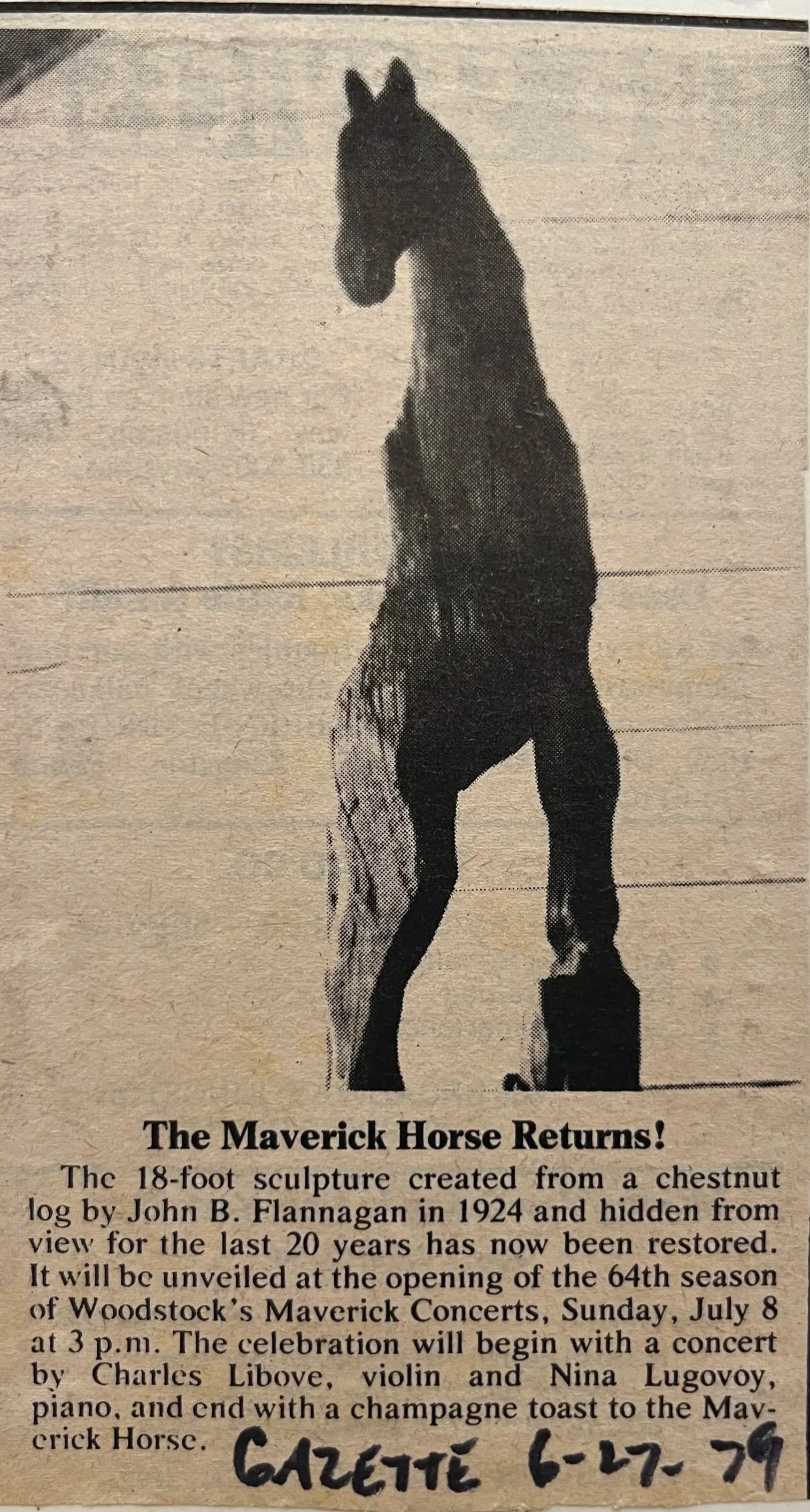

We drove by the Maverick Concert Hall to take a look at the Bohemian architecture and use of wood in its construction. Michael wondered what wood may have been used for the Maverick Horse, an iconic sculpture by John Flanagan that resides in the Concert Hall.

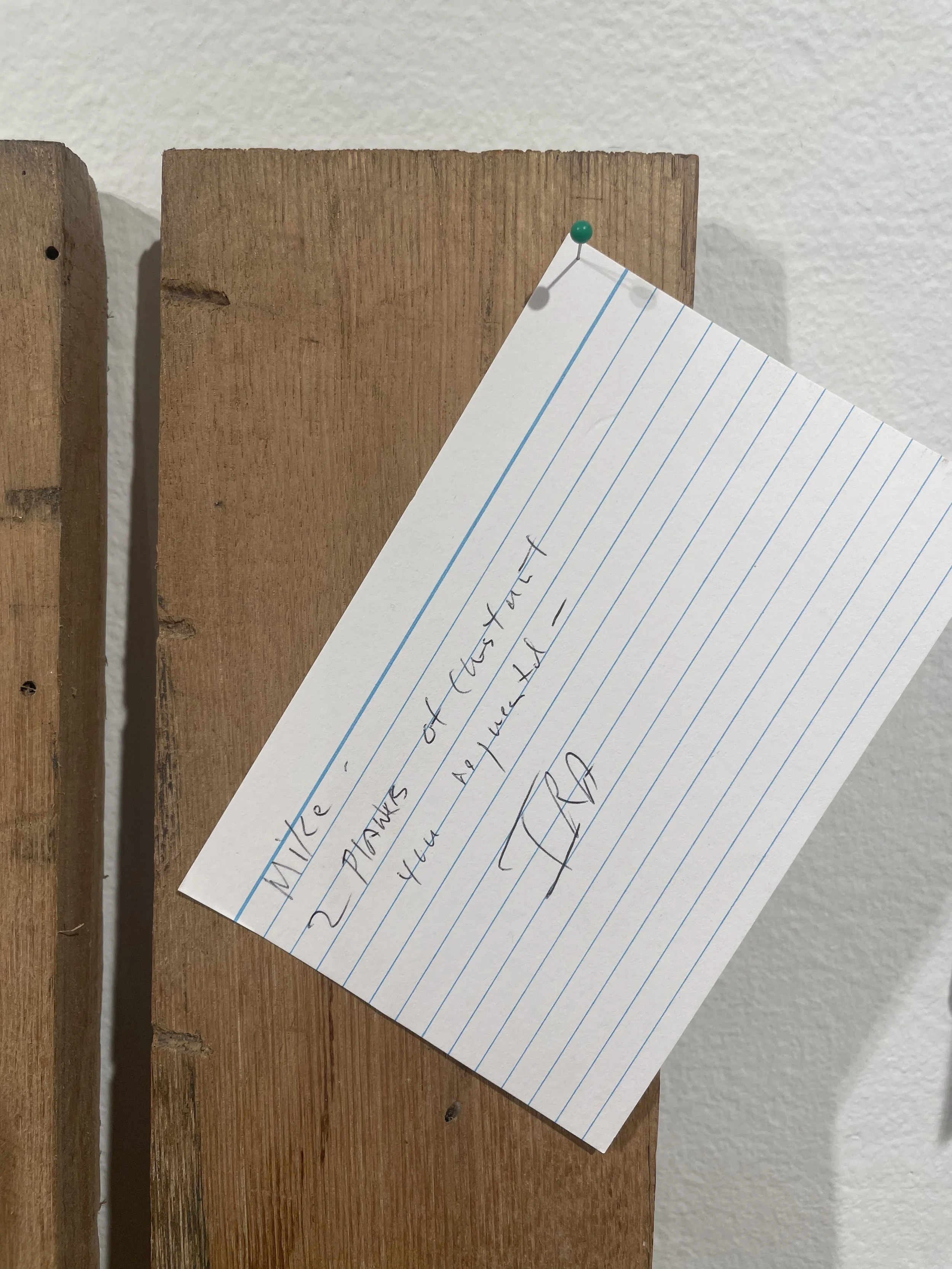

An enormous privilege of working in the YES Gallery is our proximity to the WAAM archive, and wonderful archivist, Emily Jones. A bit of digging through the archives revealed that the Maverick Horse was crafted from American chestnut! One article describes the work as being carved from a “hollow log.” Given that the sculpture was made in 1924, it seems probable that dead, blighted chestnut was readily available.

Week Three:

This Thursday we decided to hike into the woods behind Byrdcliffe. Like nearby Overlook Mountain, the lower slopes of Mount Guardian are Eastern hemlock-dominant, and faring badly. Fallen trunks and limbs piled up on the forest floor. The canopy is opening as the dying hemlocks lose their afflicted needles and branches. Some young hardwoods are growing into the gaps.

We hoped to see American chestnut sprouts. We struggled to find any at first, and noted that the environment was different in some ways from the places we’ve seen them before. On Overlook, around the Vernooy Kill in Warwarsing, and in the Mohonk Preserve near New Paltz, chestnut always appears alongside mountain laurel. We ascended the trail further, and just as mountain laurel entered the landscape, we spotted our first American chestnut. Then another, and another, in close proximity. We wonder if this is the former site of a chestnut grove.

A living sprout and dead sprout coming from the same stump, surrounded by mountain laurel.